Resistance Exercise Physiology & Skeletal Muscle During Energy Restriction

Understanding the physiological mechanisms of muscle preservation through mechanical loading in conditions of reduced energy availability.

Understanding the physiological mechanisms of muscle preservation through mechanical loading in conditions of reduced energy availability.

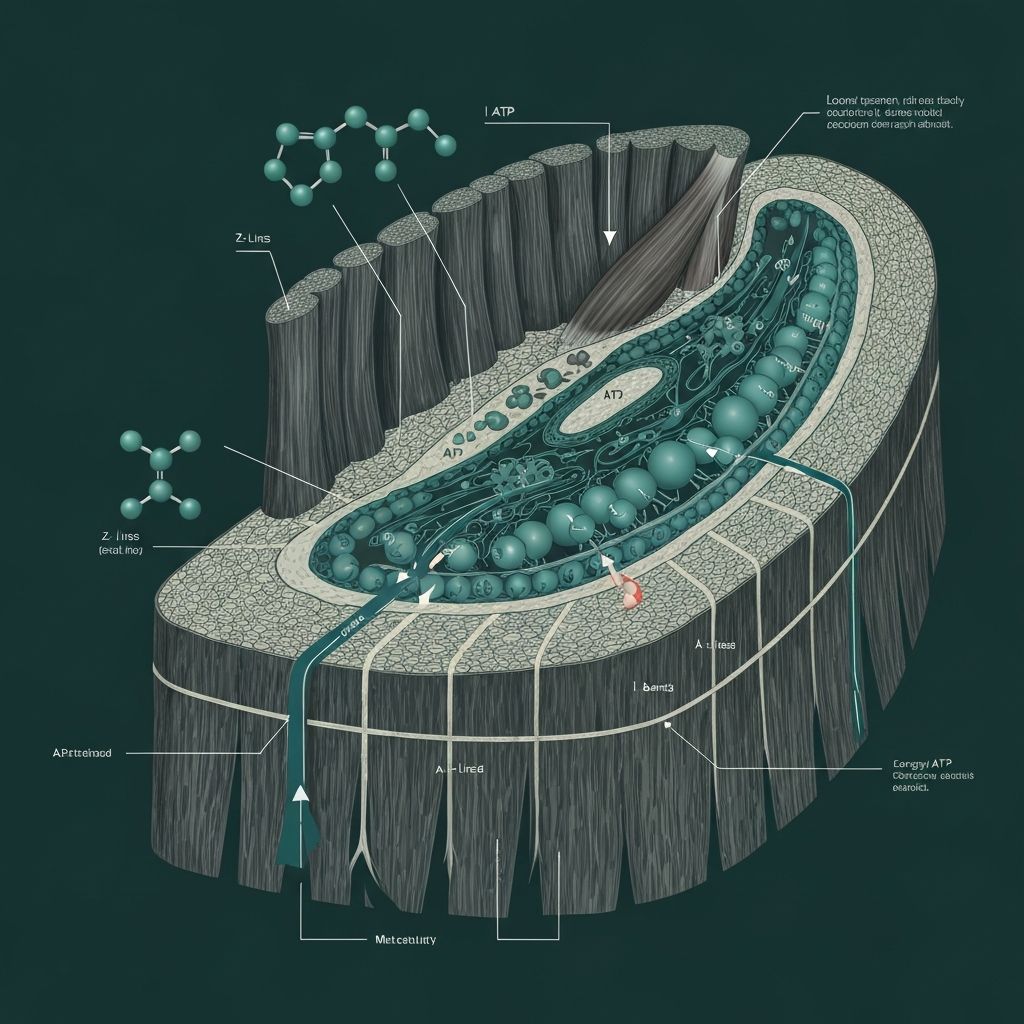

During energy restriction, the human body undergoes significant metabolic adjustments. Skeletal muscle is particularly vulnerable to atrophic processes driven by two primary mechanisms: a marked reduction in myofibrillar protein synthesis and a relative or absolute increase in proteolytic degradation.

The reduced energy availability signals the body to down-regulate anabolic pathways while simultaneously activating catabolic systems. This creates an unfavorable balance in muscle protein turnover, favouring breakdown over synthesis. The magnitude of muscle loss depends on the severity and duration of the energy deficit, the level of physical activity, and nutritional factors, particularly protein intake.

Resistance exercise creates a distinctive stimulus: mechanical tension on skeletal muscle fibres. Even in the context of systemic energy restriction, this mechanical stimulus can partially preserve or restore anabolic sensitivity.

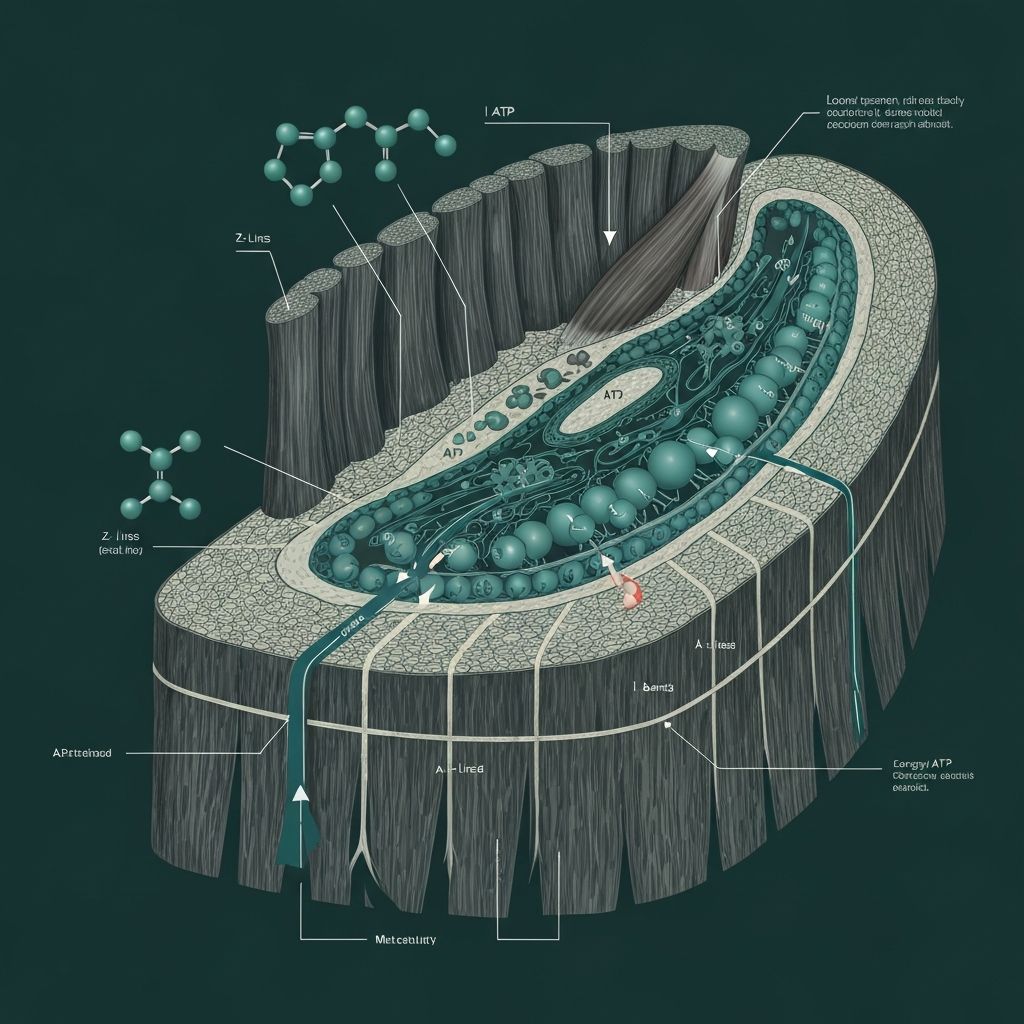

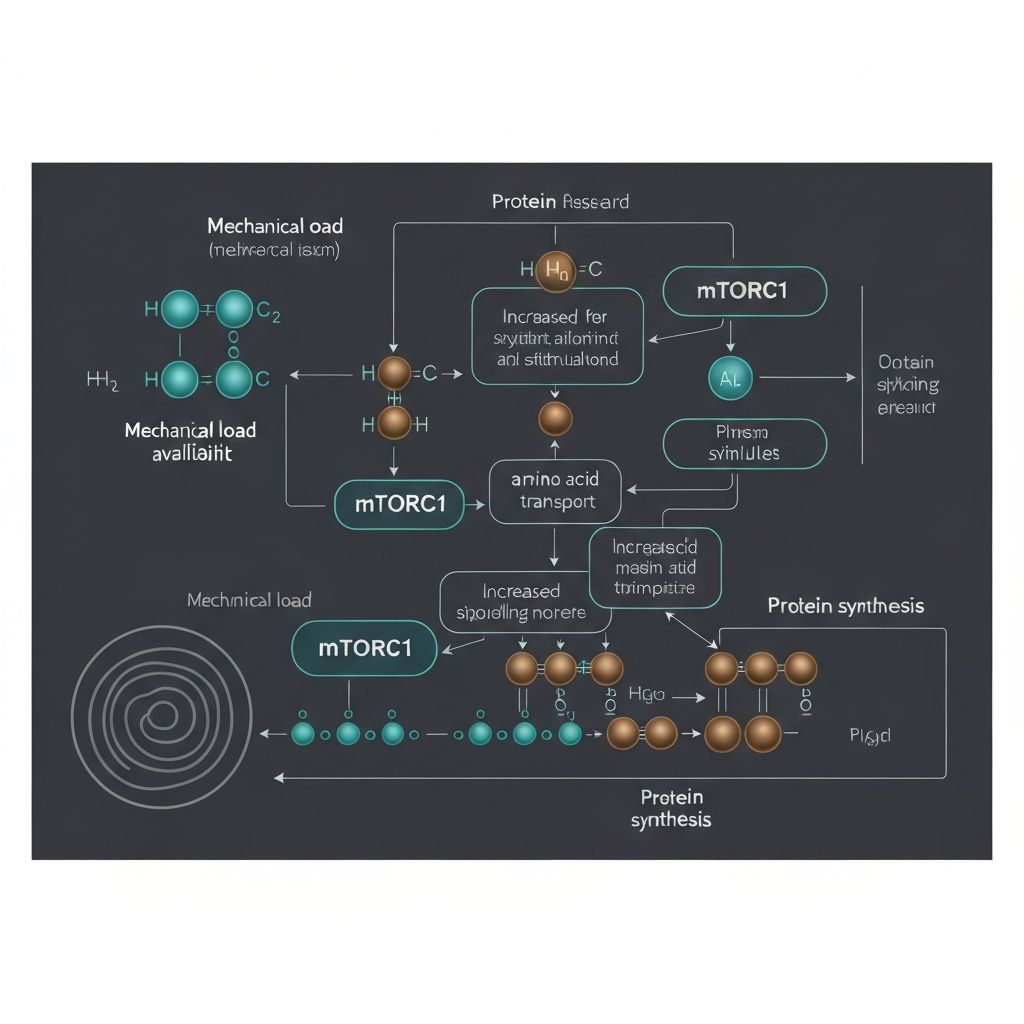

When muscle tissue is subjected to significant mechanical load, it triggers the activation of the mTORC1 (mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1) pathway. This pathway is central to myofibrillar protein synthesis regulation. mTORC1 activation occurs through mechanotransduction mechanisms, including stretch-activated ion channels, alterations in cellular fluid dynamics, and changes in creatine phosphate metabolism.

The importance of this response is that mechanical signalling remains partially functional even during energy deficit, allowing the muscle to maintain or amplify its sensitivity to anabolic stimuli compared to sedentary restricted conditions.

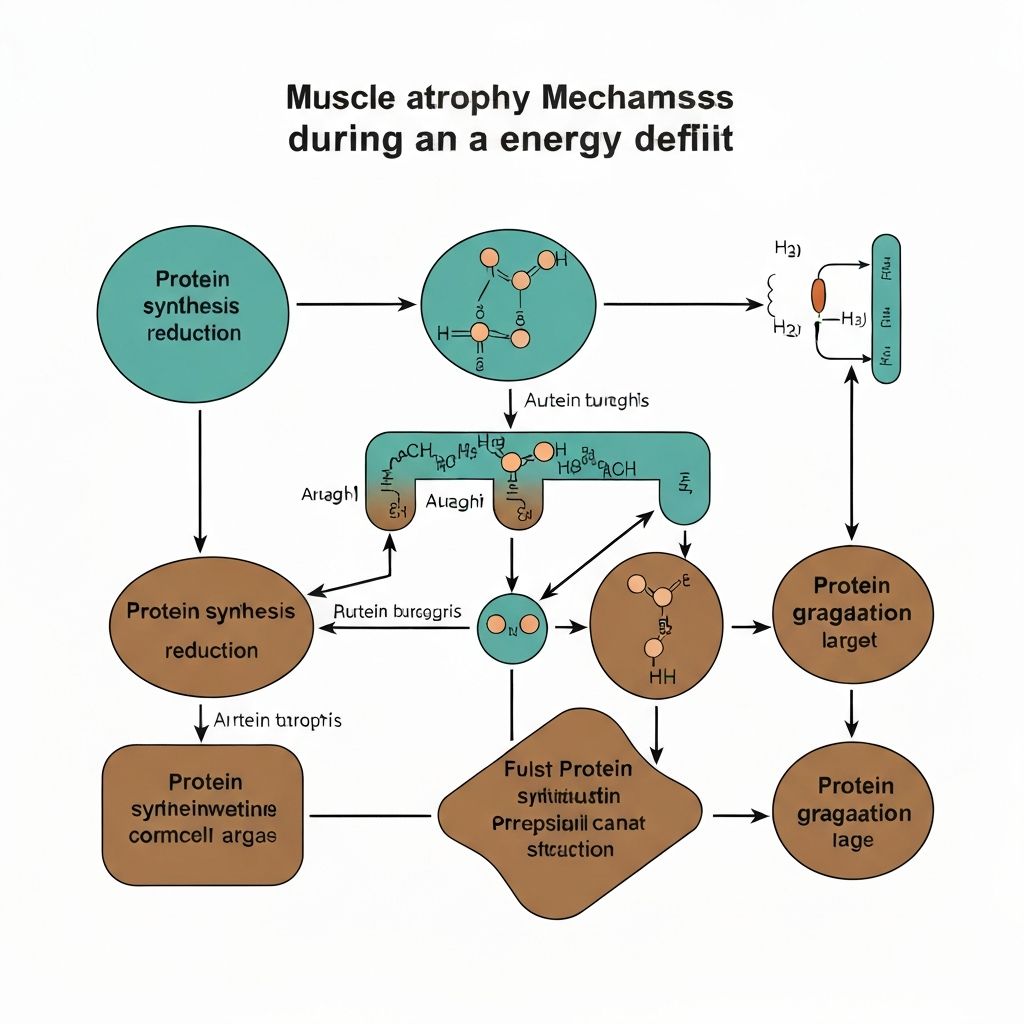

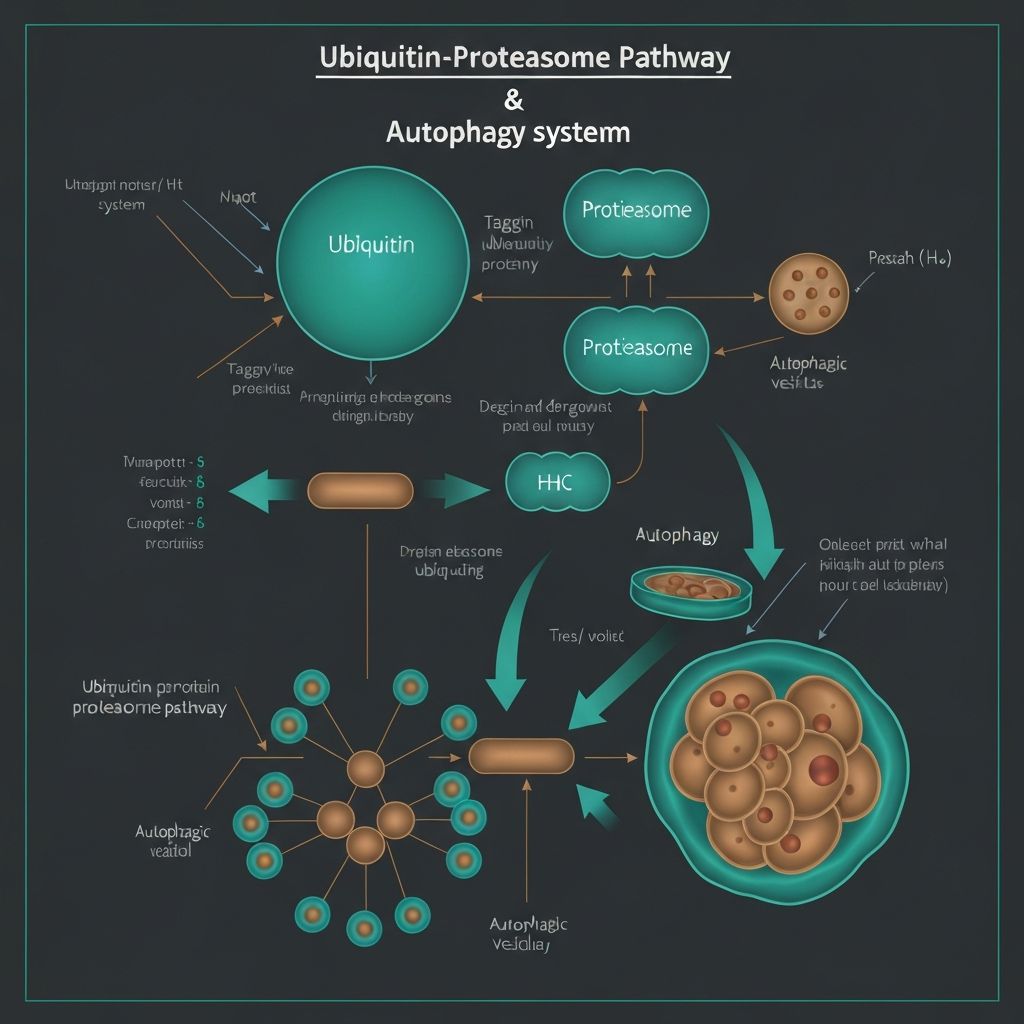

Muscle protein degradation during energy restriction occurs primarily through two interconnected systems: the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and macroautophagy.

The UPS targets myofibrillar proteins for degradation after they are tagged with ubiquitin chains. This system is regulated by the FoxO transcription factor family, which becomes activated during energy deficit and increases the expression of muscle-specific ubiquitin ligases: atrogin-1 (MAFbx) and MuRF1. These ligases orchestrate the polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of contractile proteins.

Autophagy, conversely, is a bulk degradation process where cellular components are sequestered in double-membrane organelles (autophagosomes) and delivered to lysosomes for hydrolysis. Both pathways are upregulated by AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) activation, which occurs when cellular energy charge is low.

One of the most critical insights from muscle physiology research is the phenomenon of anabolic resistance during energy deficit. Despite adequate amino acid availability, the rate of myofibrillar protein synthesis is blunted in a hypocaloric state.

However, resistance exercise creates a powerful exception to this pattern. The mechanical stimulus from resistance training significantly enhances the sensitivity of muscle tissue to anabolic signals—including amino acids, insulin, and IGF-1—even within a restricted energy environment.

This is mediated by mTORC1-dependent mechanisms and involves the activation of downstream effectors such as S6K1 (ribosomal S6 kinase 1) and 4E-BP1 (eIF4E-binding protein 1), which directly enhance the rate and efficiency of translation initiation and elongation. The net result is that muscles subjected to resistance training show elevated myofibrillar protein synthesis rates compared to non-trained muscles, even under identical energy deficit conditions.

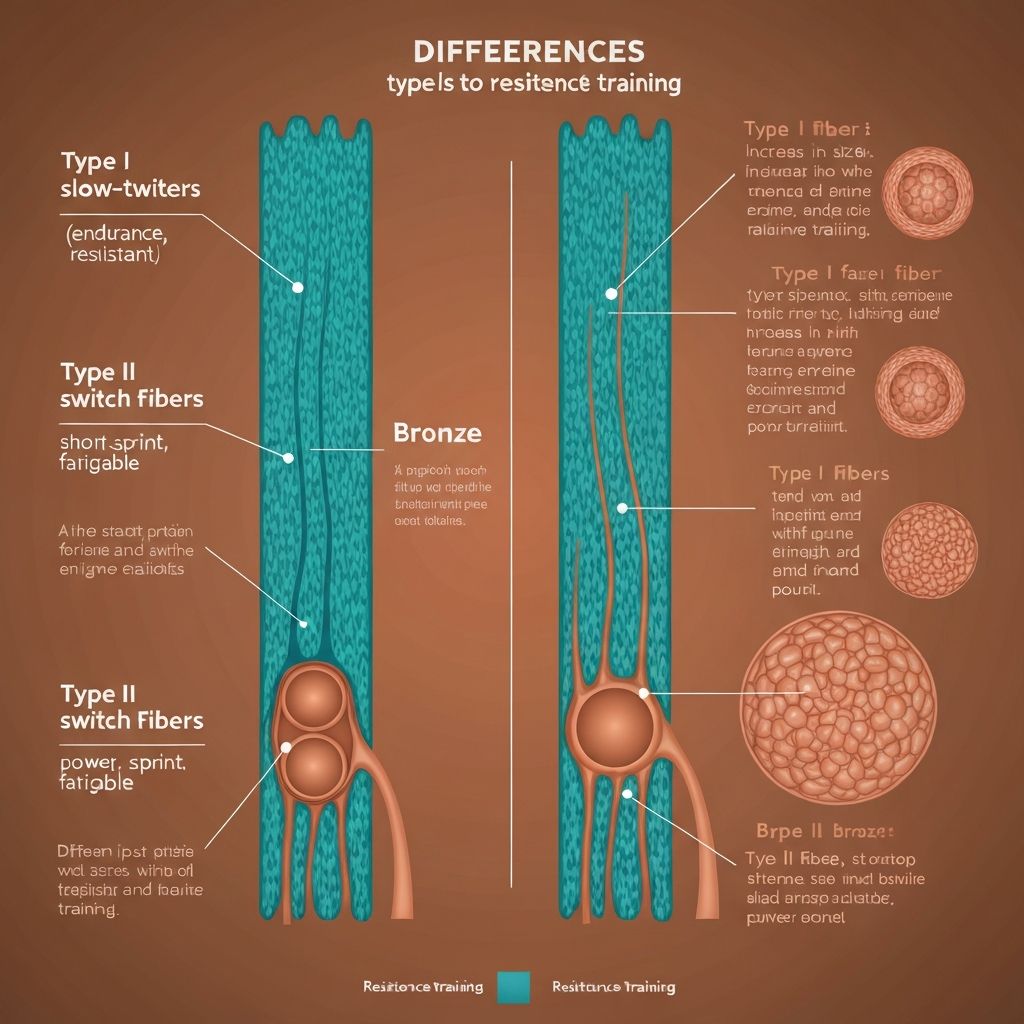

Skeletal muscle is heterogeneous, composed of distinct fibre types with differing metabolic and contractile properties. Type I fibres are oxidative, slow-contracting, and fatigue-resistant. Type II fibres (subdivided into IIa and IIx subtypes) are more glycolytic, fast-contracting, and prone to greater atrophic loss during periods of disuse or energy restriction.

During energy deficit alone, Type II fibres are preferentially lost, potentially due to their lower oxidative capacity and reduced constitutive protein synthesis rates compared to Type I. However, when resistance exercise is performed concurrently with energy restriction, Type II fibre atrophy is substantially attenuated. This preservation is attributed to the greater mechanical loading experienced by Type II fibres during high-effort resistance activities and the recruitment patterns inherent to such exercises.

Longitudinal studies of muscle biopsy samples from individuals undergoing combined energy restriction and resistance training show that Type II fibre cross-sectional area and myonuclei content are better preserved than in restriction-alone conditions, suggesting a protective effect of mechanical loading on these metabolically vulnerable fibre populations.

The preservation of skeletal muscle during energy restriction is optimised at the intersection of two factors: mechanical loading stimulus and adequate amino acid availability.

While resistance training enhances protein synthesis sensitivity, this response is still contingent on the provision of sufficient amino acids. In the context of energy restriction, protein intake becomes a critical variable. Studies indicate that protein intake in the range of approximately 1.6–2.2 g/kg body weight per day supports better muscle retention during hypocaloric states when combined with resistance training, compared to lower protein intakes.

The synergy between mechanical load and amino acid availability operates through overlapping signalling cascades. mTORC1, the central hub of anabolism, is activated both by mechanical stimuli and by leucine (an essential branched-chain amino acid). This convergence means that the combination of resistance exercise and adequate protein creates a multiplicative, rather than merely additive, protective effect against muscle loss.

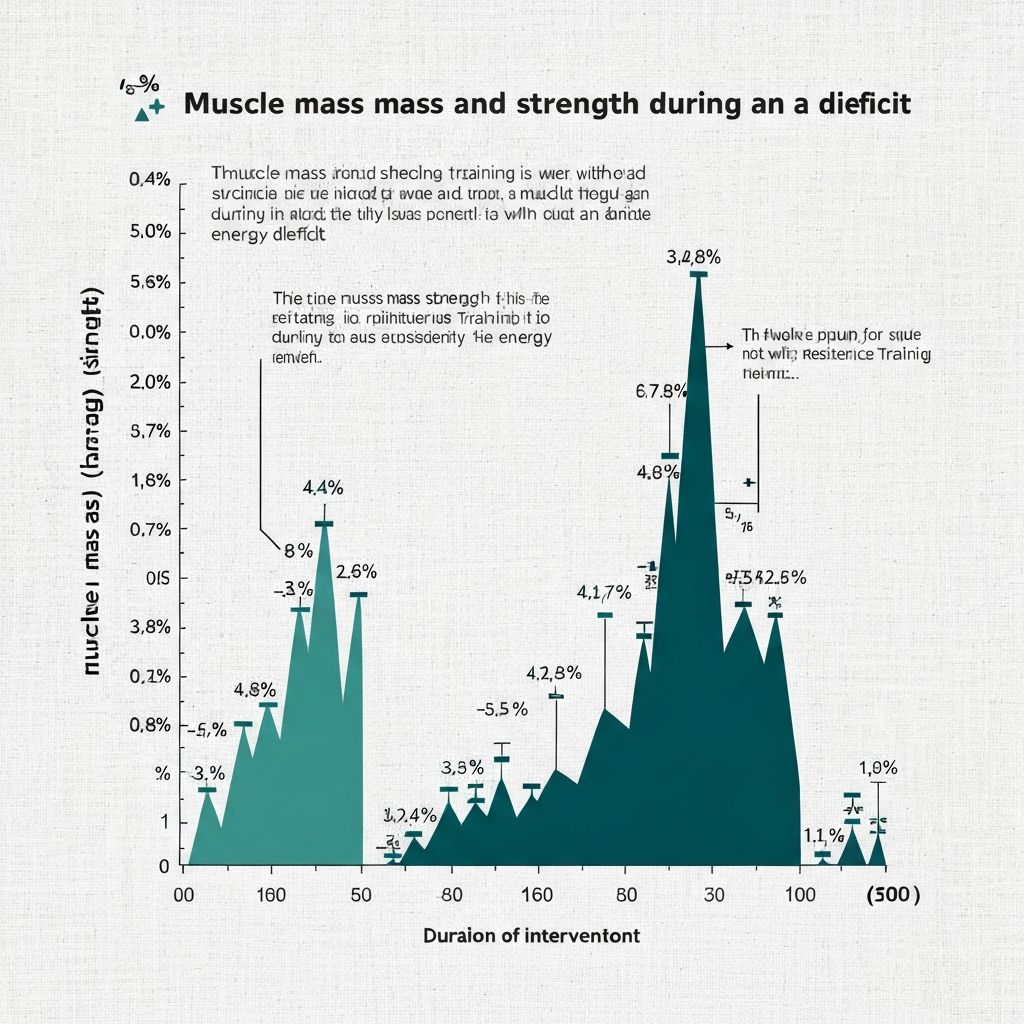

Controlled trials comparing muscle mass and strength retention across different interventions provide empirical evidence for the protective effects of resistance training during energy restriction.

| Study Condition | Duration | Lean Mass Change (%) | Strength Change (%) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Deficit Alone | 8–12 weeks | −4 to −8% | −10 to −15% | Substantial losses in both muscle mass and function |

| Energy Deficit + Resistance Training | 8–12 weeks | −1 to −2% | +5 to +10% | Marked attenuation of lean mass loss; strength maintained or increased |

| Energy Deficit + Resistance + Adequate Protein | 8–12 weeks | −0.5 to +1% | +8 to +15% | Near-complete preservation of muscle; strength gains observed |

| Weight Stability + Resistance Training | 8–12 weeks | 0 to +2% | +10 to +20% | Muscle gain and strength gains in anabolic state |

The data consistently demonstrate that resistance training substantially mitigates muscle atrophy during energy deficit. The protective effect is further enhanced by adequate protein intake, and the combination of these two factors produces outcomes approaching those of weight-stable conditions.

Explore the molecular mechanisms of mTORC1 pathway activation and its role in preserving anabolic capacity during caloric deficit.

Read the detailed physiological explanationUnderstand the ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy pathways that drive muscle protein degradation in energy deficit conditions.

Learn more about the evidenceExamine how Type I and Type II muscle fibres respond differently to combined mechanical loading and energy restriction.

Explore resistance exercise researchInvestigate the mechanisms by which mechanical loading enhances protein synthesis rates and sensitivity during hypocaloric states.

Continue to related muscle physiology topicsDiscover how the synergy between mechanical stimuli and protein intake optimises muscle preservation during energy deficit.

Read the detailed physiological explanationReview trial data and longitudinal findings on muscle mass and strength changes with combined resistance training and energy restriction.

Learn more about the evidenceMuscle loss during energy restriction occurs due to a mismatch between protein synthesis and degradation. The body reduces the rate of myofibrillar protein synthesis while upregulating proteolytic pathways (ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy) to mobilise amino acids for gluconeogenesis and other vital functions. This creates a net catabolic state in skeletal muscle.

This resource provides evidence-based information on the physiological mechanisms governing skeletal muscle during periods of reduced energy availability. Navigate to the detailed articles to deepen your understanding of how mechanical loading, protein availability, and intracellular signalling interact to influence muscle preservation.

Learn more about the evidence